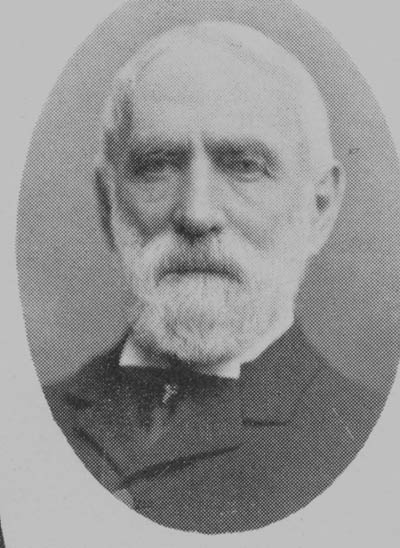

Nathaniel William Levin was born in London, England,

on 4 May 1818, the son of William, a Jewish merchant, and Frances Levin.

At 21 years of age, after training in his father's business, he sailed to Australia, taking family capital to set up as a trader. In Sydney he met Abraham Hort junior, a merchant and auctioneer in Wellington. They arrived in Port Nicholson (Wellington) on the Arachne on 30 May 1841.

Within two months Levin and Company was selling drapery, hosiery and haberdashery from the firm's first premises on Lambton Quay; Levin's long wharf provided berths for small sailing ships. Before long another store was established in Willis Street. In 1843 Levin began importing food and liquor and exporting whale oil and whale bone. He purchased a shore whaling station at Cloudy Bay, but this venture was short lived. His social and economic standing enabled Levin to become a foundation member of the Wellington Club in 1841.

On 3 January 1843 Abraham Hort senior, his wife and five daughters arrived from England, authorised by the Chief Rabbi to form a Jewish Congregation. Levin was one of those who petitioned Governor Robert FitzRoy for land for a Jewish cemetery and synagogue and, after a grant was made, he became a trustee. Levin married Jessy Hort, daughter of Abraham Hort senior, probably on 31 July 1844.

Between 1845 and 1847 Levin and the younger Hort shipped goods and passengers to Tahiti. In 1847 Levin and Company became established as a shipping and land agency. By 1848, as sheepfarming began to replace whaling, Levin started to ship in wool from coastal stations and send it to England. Exports grew rapidly. By the early 1850s the company was established as a general merchant and stock and station agent. The discovery of gold in California and Australia prompted Levin, together with Samuel Revans and John Jury, to ship supplies to San Francisco in 1850, and across the Tasman in 1852.

Levin was a member of the first committee of the Wellington Chamber of Commerce in 1856; 11 years later he became president. In 1862 he refused a seat on the Legislative Council; his energies were focused on his business and he wished to go to England. Before his departure in June 1862 he went into partnership with Charles Johnson Pharazyn. After the Levins returned in May 1864 the firm acquired agencies for the Victoria Fire and Marine Insurance Company of Melbourne and, in 1866, for the New Zealand Trust and Loan Company.

His hopes of great progress in the 1860s were not realised. He became increasingly depressed as racial hostility increased. 'Native affairs are looking very gloomy and I fear nothing but almost the entire destruction of the race will ever settle the question'. To add to his woes, gold production was falling, prices for wool slumped, and the colony's credit was depressed. By October 1866 business failures were 'rife' in Wellington and the banks were 'putting on the screws'. Levin noted that although he was 'not a loser to any amount still the utter stagnation of business makes one very anxious added to which my health is anything but good'.

He resolved to retire to England within two years. Cares and anxiety were 'fast destroying' his health, he did not wish his only daughter Anne 'to grow up as the girls of this country' and, quite simply, he was 'tired of colonial life'. His resolve was strengthened by his disgust with politics. He seldom visited the House of Representatives, but when he did it was 'to return with the desire to get out of the country as quick as possible'.

In March 1868 the partnership between Levin and Pharazyn was dissolved. The business was to be carried on by his eldest son, William (Willie) Hort Levin, in partnership with Charles Pharazyn and Walter Woods Johnston. Levin retained an office in the company's premises and did some buying and selling of wool on his own account. In June 1869 he accepted an appointment to the Legislative Council, the first Jew to become a member. Possibly out of disdain for the proceedings, he never made a speech. Within 18 months he had resigned, after being absent from the colony for more than a year.

In 1869, as Levin was preparing to go to England, he became the centre of a sensational scandal. He took action for slander against Richard Beaumont, who had accused him of conspiring with Joseph Dresser Tetley, a sheepfarmer with vast landholdings in Marlborough, to swindle him. Beaumont was one of four young Englishmen who had been advised by Levin to invest their capital with Tetley. By 1868 the four had invested £22,000 in a company, with Tetley as managing director. But that year Tetley disappeared without trace. All of the Englishmen's capital had gone; Levin and Company had lost £15,000 and Levin personally £6,000.

A bitter Beaumont accused Levin of colluding with Tetley to entice the four to lend their money so that Tetley's overdraft with Levin might be liquidated. Levin sought vindication because he had been 'injured in his credit and reputation as a merchant and agent'. After a widely publicised three day trial at Nelson, the jury was unable to agree and the parties eventually consented to their discharge without a verdict. Although it is clear that Levin did not conspire with Tetley, he had become increasingly concerned when Tetley defaulted on his debts, and he failed to warn Beaumont and his associates. This failure, and his willingness to preserve himself at their expense, could be regarded as sharp practice.

One month after the trial, on 27 December 1869, Levin left for England with his wife and daughter. He was farewelled by 50 prominent men at the Wellington Club. They expressed sympathy at 'the unfounded attack which had been made on his character at the close of his long and honourable career'. In London Levin became a partner in the firm of Redfern Alexander and Company, who had been his agents for many years. He retired in 1882 and died on 30 April 1903, attended by his son-in-law, George Beetham. His wife, Jessy Levin, survived him by one year.

At the time of his death, even though much of his colonial property had been passed on to Willie and his family, Levin still had assets in New Zealand worth £104,818. And although he was Jewish, his wealth had gained him acceptance into the ranks of the colonial élite. He cultivated business and family contacts with such leading men as Frederick Weld, Charles Clifford and George Grey. When his second son, Lionel, aspired to a military career in England, Levin secured Grey's patronage and urged the youth to befriend Clifford because of 'the interests he holds in society in England'. Levin was a loving and understanding father but he demanded excellence from his sons. He succeeded financially and socially not only because he arrived early with money and mercantile experience but also because he was quick to seize opportunities and was single-minded in pursuit of his goals.

ROBERTA NICHOLLS

Goldman, L. M. The history of the Jews in New Zealand. Wellington, 1958

Gore, R. Levins, 1841--1941. Wellington, 1956

Levin, N. W. Outward correspondence, 1866--1868. In Levin & Co. Records, 1839--1961. MS Papers 1347. WTU

Millar, J. H. The merchants paved the way. Wellington, 1956

Nicholls, Roberta. 'Levin, Nathaniel William 1819 - 1903'. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, updated 7 April 2006

URL: http://www.dnzb.govt.nz/

The original version of this biography was published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Volume One (1769-1869), 1990

© Crown Copyright 1990-2006. Published by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Wellington, New Zealand. All rights reserved.